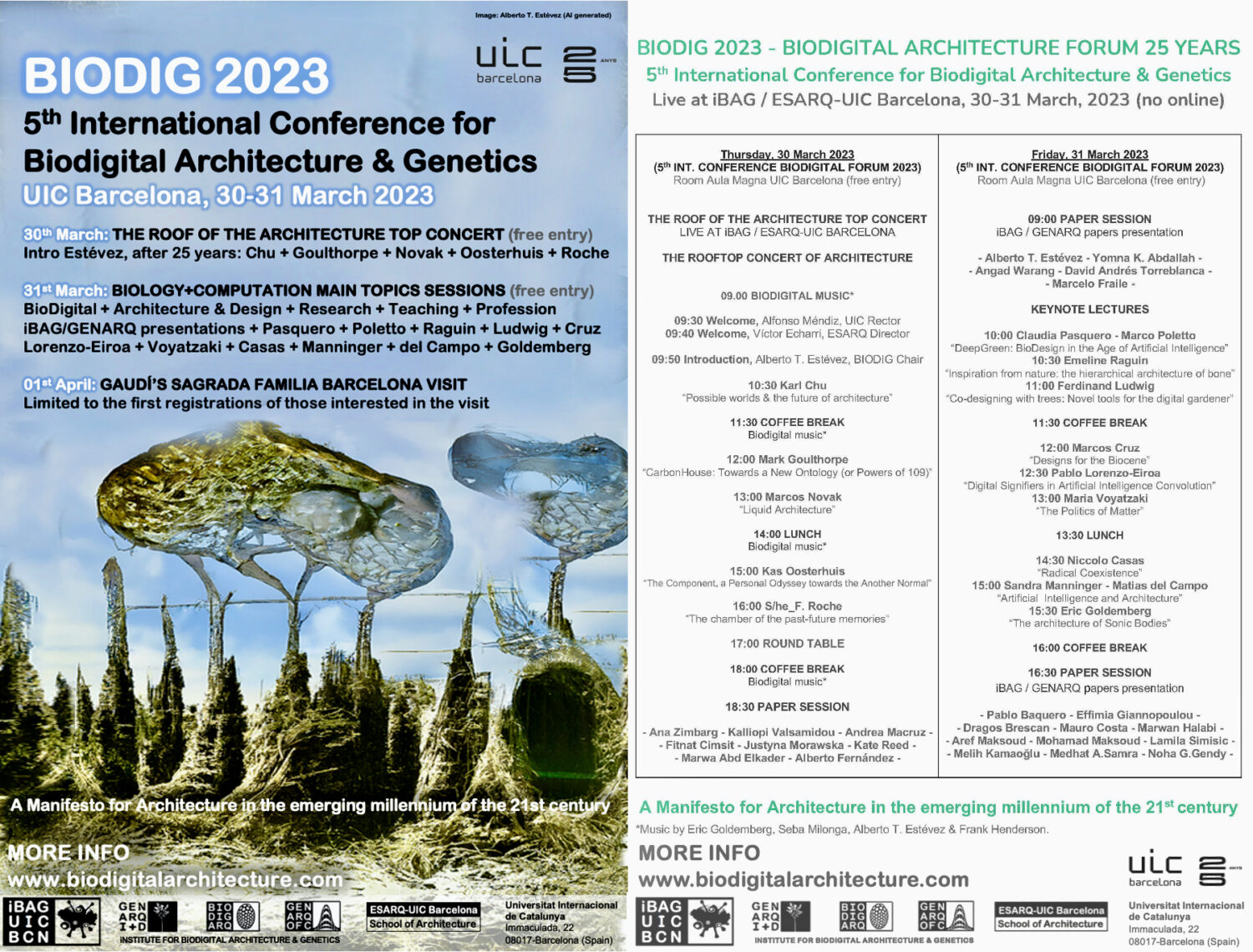

Summary lecture “The Component” by Kas Oosterhuis

My new book is titled “The Component, a Personal Odyssey towards Another Normal”. Complex active components – as opposed to static elements – act as well-informed and unique building parts that establish a real time relationship with their immediate neighbors, as do birds in a swarm. Complexity is an emergent property of simple rules: complex but not complicated. My personal odyssey wanders from earlier realised projects that are based on mass-production methods to featured realised projects [Saltwater Pavilion, iWEB A2 Cockpit, Bálna Budapest, Liwa Tower Abu Dhabi] which are based on radical parametric design to robotic production methods, and – its ultimate destiny – to projects that display real time behavior, changing shape and content in real time, which is the default condition of ubiquitous digitalization in the Another Normal. Nomadic international citizens are the inhabitants of the Another Normal. The Another Normal is as of now a hypothetical parallel world. Urged by the climate crisis, the food, energy, and water nexus, the COVID-19 pandemia, and the current AI storm, the Another Normal demonstrates the inevitable data-driven techno-social architecture of the physically built environment and the metaverse. Besides robotic production on demand of almost anything – when, where, and as needed – I propose strategies that run in parallel to establish the Another Normal, among others: ubiquitous basic income, global birthright to own a generous piece of land, distributed production of healthy food, clean energy and drinking water, ownership of private data and personal avatars in the web 3.0, autonomous electronic transportation, ubiquitous shared responsibility for clean production and waste treatment techniques, ubiquitous home delivery, working from anywhere for any period of time, decentralised real time peer to peer banking, enhanced by benign algorithms and verified AI technology. The organic real and the synthetic hyper-real co-evolve naturally in the Another Normal, where simple rules create complexity, diversity, fairness, and equality. Choosing only those strong and simple rules that lead to diverse and complex outcomes. The Component, a Personal Odyssey towards the Another Normal has 10 chapters: 1] Here and now, 2] What have we done? 3] Another Normal, 4] Ubiquitous components, 5] Components versus elements, 6] The Component, 7] Where are we now?, 8] Proactive components, 9] Where do we go?, 10] The Chinese Patient. The Chinese Patient chapter suggests a set of 12 simple rules of law that are meant to form the framework for diversity, fairness, and justice in the built environment.

Although supple in its geometry, our work is not a form of biomimicry. In art, expressionism cleared the way to abstract art, which in its turn paved the way for concrete art. Concrete art is an art form that needs neither reference to organic nature nor to man-made artefacts. Concrete art is what it is, its meaning lies in the eyes of the beholder. Similarly, my architecture is what it is, incorporating the actual state of affairs with respect to culture and technology. Back in the late eighties, early nineties, visual artist Ilona Lénárd and I explored the alien by a design method we called Artificial Intuition, sketching without predefined ideas in digital weightless space. During the process of sketching one responds to what is evolving before one’s eyes, and afterwards one decides what meaning one could give to the sketch. There are a few parallels to how today Artificial Intelligence is used to create images, with one important difference: we do not draw from a database of existing 2D images, but create a 3D construct directly from our own brains through intuitive gestures. While Artificial Intelligence-generated images I consider a form of modern alchemy, our design method is synthetic in nature, leading to precise verifiable constructs. We are not depending on someone else’s biases in the selection of images, we are diving “idiot-savant-style” into a universe that is developed by ourselves, into our own biased visual and gestural repository. Artificial Intuition has proven to be the fertile basis for all of our work from then on, anticipating the building body and real time behaviour of the Saltwater Pavilion, which opened its gullwing “doors” in 1997.

Working on Ilona’s Folded Volume, exhibited in the Synthetic Dimension exhibition in 1991, we discovered the crucial role of parametric design and component-based construction. The heavily cantilevering shape of Folded Volume is assembled from a dozen different components, irregular triangles, an irregular quadrangle, a pentagon and a hexagon, connected to their nearest neighbors following one and the same parametric detail. Our design adage “One Building, One Detail” was born. It lasted until 2001, designing and building the Web of North-Holland, to unleash the uncompromising design philosophy to the scale of architecture. In its appearance, the Web of North-Holland we consider both a work of art – that is when the gullwing doors are closed – and a piece of architecture – that is when the giant hinged sections of the skin open up to invite the public into the building. Neither the shape of Folded Volume, nor the shape of the Saltwater Pavilion, nor that of the Web of North-Holland, refers to anything in particular. These objects are what they are, which in an unfamiliar fashion makes them look alien. They look closed from the outside, yet regularly open up dramatically to reveal to the public their out of the ordinary interactive interior. Not surprisingly, our sculpture buildings are often seen as spaceships, which is a reference I would accept, since, just like spaceships, our projects are designed in weightless space, make precise contact with the local context and then adjust to that context before they make a successful landing. But I certainly would not accept the reference of the Bálna Budapest as a whale – “bálna” meaning “whale” in Hungarian. Our building was originally named the CET [Central European Time], which had the second meaning of “whale-like”. The general public quickly nicknamed the building the Whale, and that reference became so popular that the building was officially renamed into the Bálna. I never intended the building to look like anything in particular. The underlying design ideas are pure abstract [aka concrete] notions of 1] going with the flow, while the building is positioned along the banks of the Danube, and points in the direction of the flow, 2] cantilevering forward to new developments to the South of Budapest as to look forward into the future, 3] feature lines that come down to exactly one point, to visually fix the volume to the to the ground in the most minimal fashion, 4] merging facade and roof into a single envelope, while the outward-pulled back and the forward leaning front of the main volume function as protective canopies above the entrances, 5] absence of traditional indications of what is a door, a window, a floor, a base, a shaft or a capital, and 6] the integration of structure and skin into one coherent system. Yet, I often refer to my buildings as “body buildings”, not as a reference to organic bodies, but to the unibodies of cars and other forward moving vehicles. However, what organic animal bodies and synthetic vectorial bodies have in common is the symmetry along its longitudinal axis. Both animal bodies and our vectorial bodies want to go places, they want to go where no one has been before.

Parametric design is a design method to build dynamic relations between the constituent parts. Parametric design is not a style as advocates of “parametricism” want us to believe, and certainly not the dominant style of our times. Yet, building dynamic relations between the constituent components of a building, between buildings in the city fabric, and between the buildings and their users is bound to become the new normal. A parametrically orchestrated design can just as well be orthogonal as fluid. Parameters are defined as variable values in an equation. However, following the design paradigm of continuous variation, the visual outcome may well become fluid, as the components of the structure and the skin may gradually grow or diminish in size, gradually change shape, smoothly transform from convex to concave, or feature folding lines that fade in and fade out. Liquid architecture – as Marcos Novak coined the term back in 1991 – may be adopted by individual designers to mark their style. Parametric design supports such a liquid, fluid design approach, as it has supported all of our designs since we designed and realised the vectorial building named the waste transfer station Elhorst/Vloedbelt in the early nineties. But is not the proper label to put on liquid architecture. Neither would it be right to label our design attitude as computer architecture or digital architecture. One should not take the means and methods of design and production to describe the architecture. Similarly, I decline terms like robotic architecture and AI architecture. Such terms are at best short-lived superficial characterisations, but fail to describe what is the design concept of the designer. Paraphrasing Frank Stella: “What you see is what you see”; it is what it is, and its meaning is in the eyes of the beholder. Microsoft’s AI assistant Bing describes my architecture as follows: “Overall, Kas Oosterhuis’s architecture is known for its innovative designs that push the boundaries of traditional architecture. His designs often feature a combination of iconic architecture and functional layouts that are cost-effective”. Innovative architecture is an until then unexplored combination of design concepts and techniques. I am not interested in establishing a particular style, my interest is in innovating architecture from within, thus generating the unknown.

Kas Oosterhuis, April 2023