In summer 1978 one year before finishing my studies at the TU Delft I wrote a letter to architect Peter Gerssen as to apply for a 3 month internship. He called me back and I came to see him in his modest mansarde roofed house with a free flowing space combined home and office in Kralingen, Rotterdam. I showed him a design for a townhouse in Amsterdam , which I did together with my friend Onno de Vries, of which design he was critical since it looked to him too typical modernist. Then at the end of the interview I picked a handmade 3d model out of my backpack [I biked 15 km to reach his home-office], which he liked instantly. This model was a much bolder statement with its silvery body featuring a vertical black glass volume jutting out of it. I was hired.

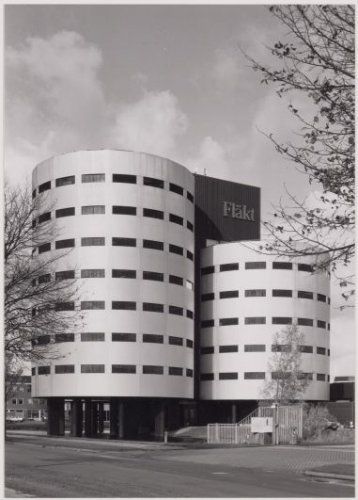

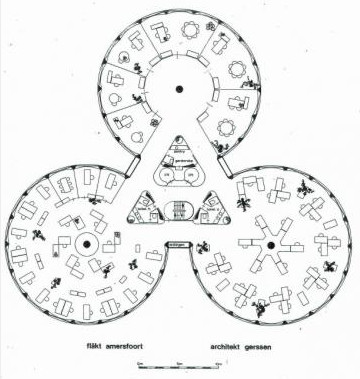

Peter Gerssen was flattered that my letter included an very positive appraisal of his revolutionary Fläkt Building [1973] featuring 3 round aluminum cylindrical volumes connected together by a triangular core. It was designed as a showcase of extreme prefabrication and smart integration of sustainable climatic concepts. Peter Gerssen worked as from the early design phase together with MEP consultant Willem Schuringa and mobility expert Ad Luitwieler. The client Fläkt was initially skeptical about the costs of the cylindrical design scheme, they did not think it would fit in their budget. Peter Gerssen revealed to me his secret how he managed to get things done. He had his technical designer Ries Marcus, whom he knew from his period as lead designer in the Rotterdam based office of the renowned architect Hugh Maaskant, draw an isometric 3D model of 3 distinct concrete components only: a central column, a pie-shaped floor element and a load-bearing wall element, and asked for a quote from prefab builders for some hundreds of exactly the same, without showing the building as whole, just the components. This is how he got the price right, don’t tell more than strictly necessary, an ultimate example of analogue lean and mean data exchange.

In his compact home office the drawing tabel where I did my job as his sole trainee, Peter Gerssen was proud to show an artisan work of his wife Carla Maaskant [yes, Hugh Maaskant’s daughter], who tragically died untimely the year before I came in. A large macrame assembly of raw rugs and colored fabric, in the form a large layered three-leafed flower, notably his inspiration for the lay-out of the Fläkt Building.

The lay-out of the floor plan is extremely efficient, short connections from stairs and elevators to offices and between office clusters, a very cool communication scheme. It also shows an early version of open office plans, with the possibility to have private offices. The 3-flight stairs are placed such that the tenants would be tempted to use stairs rather then the elevators, a strategy that now has become mainstream as to enhance people’s mobility and hence their health. The interplay of shafts, sanitary units, elevators, stairs and fire resistant doors on electromagnets is absolutely brilliant. The facade is clad in 6 mm thick bent aluminum plates, is effectively acting as a solar radiation shield, in combination with relatively small windows – yet providing for a generous panoramic view – reducing the incoming heat drastically. The energy performance of the Fläkt Building was unheard of in 1973. Even now it would easily earn its LEED platinum rating.

The Fläkt Building is well on its way to become a modern monument, 6 years to go before it has reached the monumental age of 50, which is the criterium in The Netherlands before a building might be declared a modern monument. The painful side of the story is that the Fläkt Building is no longer in use since years because its location in a rather desolate industrial area is no longer a desired one, meaning that it the building is in real danger of being demolished.

During my internship I got the task to make shop drawings for his new invention: the Stolpwoning. A “stolp” in Dutch is the bell shaped cover to protect food like cheese from flies. His vision was to design a truly prefabricated home, using wooden sandwich elements for floors and walls alike. The geometry of the Stolpwoning basically is a cube cut in half over the diagonal, which results in a hexagonal floor plan. To draw and calculate the trapezoid elements in horizontal plan, featuring 45 degrees chamfer where they connect in the edges of the cube, was a very precise engineering task, which I enjoyed to do and executed almost without failures using a technical calculator. At that time in the late seventies I started experimenting with CAD software on large mainframe workstations, but it was not yet feasible to get a proper positioning of the diagonally cut cube on the horizontal plane, tilted as to form the hexagonal basis of the house, and hence to make proper working drawings. What we actually did was analogue file to factory, design to production avant la lettre. Design and the engineering were the same thing, the details from the materials and the technology how to compose the well insulated sandwich elements directly informed the design process.

Gerssen has delivered hundreds of his Stolpwoningen, 3 of them executed as an assembly of 10 cm steel sandwich panels with high insulation polyethylene foam, for floors and interior / exterior walls, while both interior and exterior finishing had the white coated steel sheet of the sandwichpanels exposed. The Stolpwoning is a most radical and true form of a prefabricated home [not a holiday home] I have ever seen, radically sustainable without any form of nostalgia.

That is why I acknowledge Peter Gerssen as my one and only great teacher.

After finishing my studies I worked with Peter Gerssen for many years, resulting in jointly designed buildings like the Zwolsche Algemeene in Nieuwegein near Utrecht [1983] and BRN Catering in Capelle a/d IJssel near Rotterdam [1987], both examples of innovative use of extreme prefabrication and innovative glass cladding systems. Zwolsche Algemeene featured Europe’s first structural glazing glass facade, for which I travelled to the USA to check out the early applications of this PPG system. On the image the pillow effect of the heat-strengthened production process is clearly visible.

The smaller BRN Catering headquarters featured – among many other innovations – a bespoke frameless open joint breathing glass shield made of in-the-mass-colored grey glass covering both the double height warehouse and the two office floors on top of the storage spaces, and built for a very competitive price. At the time BRN Catering was the most energy efficient building in The Netherlands. BRN Catering was the first [and the last] building where we collaborated as partners in business.