Do by Dutch

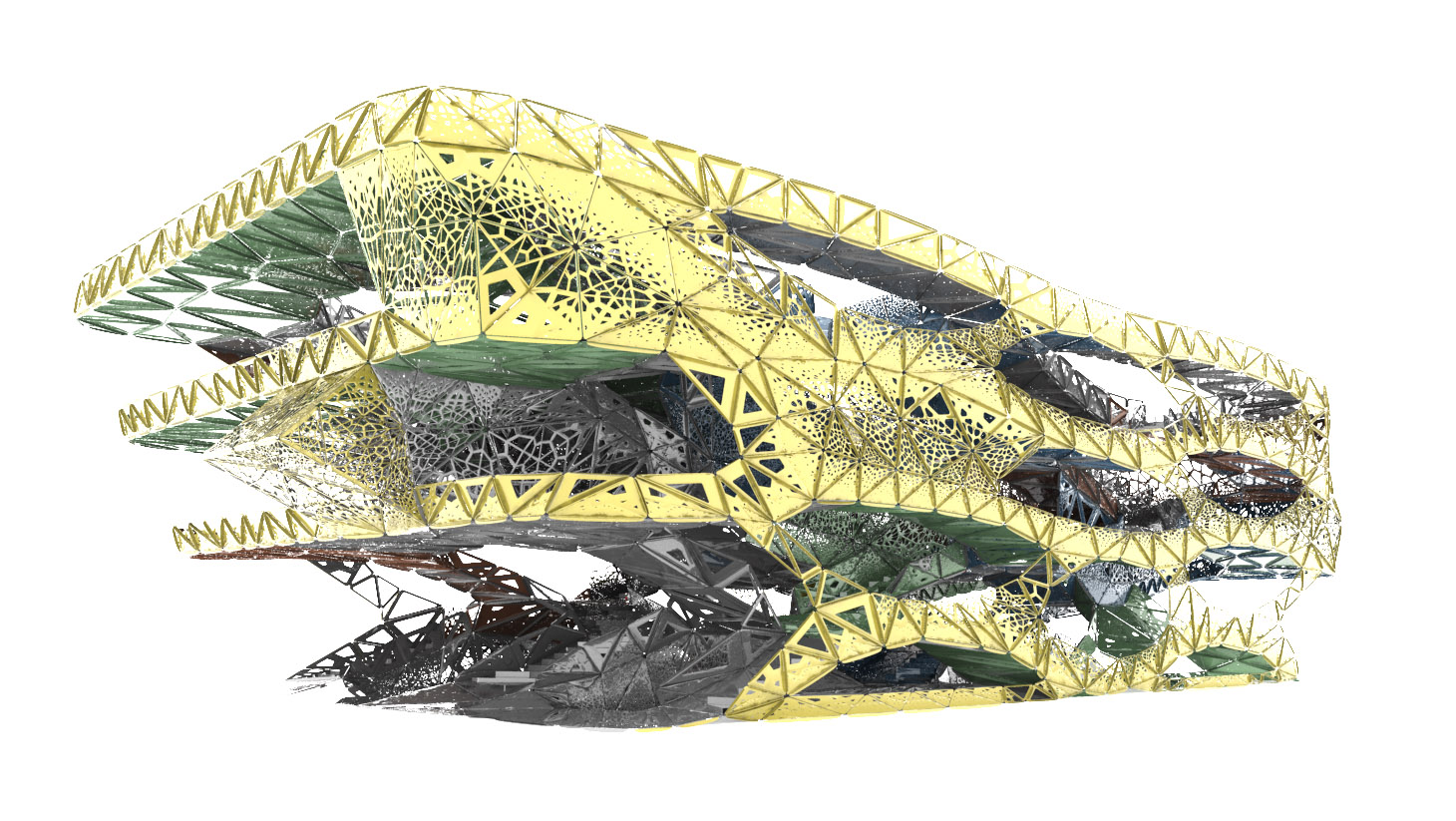

The design task we set for ourselves for the design of the Dutch Pavilion for the World Expo 2020 in Dubai, which we nicknamed Do By Dutch, pronounced as Dubai Dutch, was manifold: 1] to design a pavilion that is fully self-supporting in terms of food, energy and water supply, 2] to design an experience for three intertwined trajectories, one showing the new developments in food production, one for energy production and one for water production and treatment, 3] to design an open natural ventilating structure that would need a minimum of cooling, and 4] to design a structure that is based on one single family of parametric components. One moldable component for the surfaces where people walk on [formerly known as floors], one parametric variation for the surfaces people are leaning to [formerly known as balustrades], one for the surfaces separating discrete spaces [formerly known as walls]. Being self-supporting does not mean that the building is not connected to a shared network for energy, water and food supply. It does mean that whatever is consumed and what is produced must be in an equivalent balance with its immediate neighbors. Being self-supportive should never be interpreted as isolating oneself from the world. On the contrary, being self-supportive means connecting oneself to the world in a fair balance to one’s immediate neighbors. Isolating oneself would mean that exchange with immediate and faraway neighbors would come to a stalemate, while a ubiquitous interconnectedness is key to building a culturally rich environment / world. Connecting to immediate neighbors means to give and to take. It means processing information of all kinds [data, food, energy, water, materials, memes, ideas] and emitting the processed information in a slightly differentiated form, modified by your own preferences.

The three interwoven trajectories have a separate entrance, as to distribute people evenly in the pavilion and to avoid long queues. The trajectories lead up to the roof where the trajectories merge together in a model well balanced environment. The three trajectories cross each other at key points halfway. The public may follow one particular trajectory or change paths and follow the other, but any personal trajectory through the three-dimensional hive is possible. The three-dimensional lay-out of the pavilion is a complex spatial web of slopes, platforms, voids, connections and experiences. From each platform one has the choice to go in two directions [at the periphery] or three other directions [in the heart of the building]. Each slope is both ramp and stair, suited for small electric vehicles to drive up the elderly and physically challenged, and for pedestrians that have no problem to use the easy walking stairs. The slopes are divided in two zones, one for the electric vehicles and one for the pedestrians. In the spatial lay-out the slopes have open voids to the right side and the left side, which adds to the transparency of the open pavilion, takes credit for surprising interior vistas and for an intense spatial experience. One enjoys views to the left, to the right, up and down, and diagonally through a series of voids. The three trajectories of food, energy and water are laid out in such a way that they are passing through all platforms. The trajectories are given their thematic touch and feel, each in their own color. The structure is totally open from all sides for natural ventilation, it offers a constant refreshing breeze for the visitors, much welcome even in the Dubai winters. The three-dimensional maze will stimulate a constant light turbulence of the air, as in a termite hill. The freshness of the air will be enhanced by spraying water droplets from the water production path. The droplets will have their effect in other trajectories that are nearby as well.

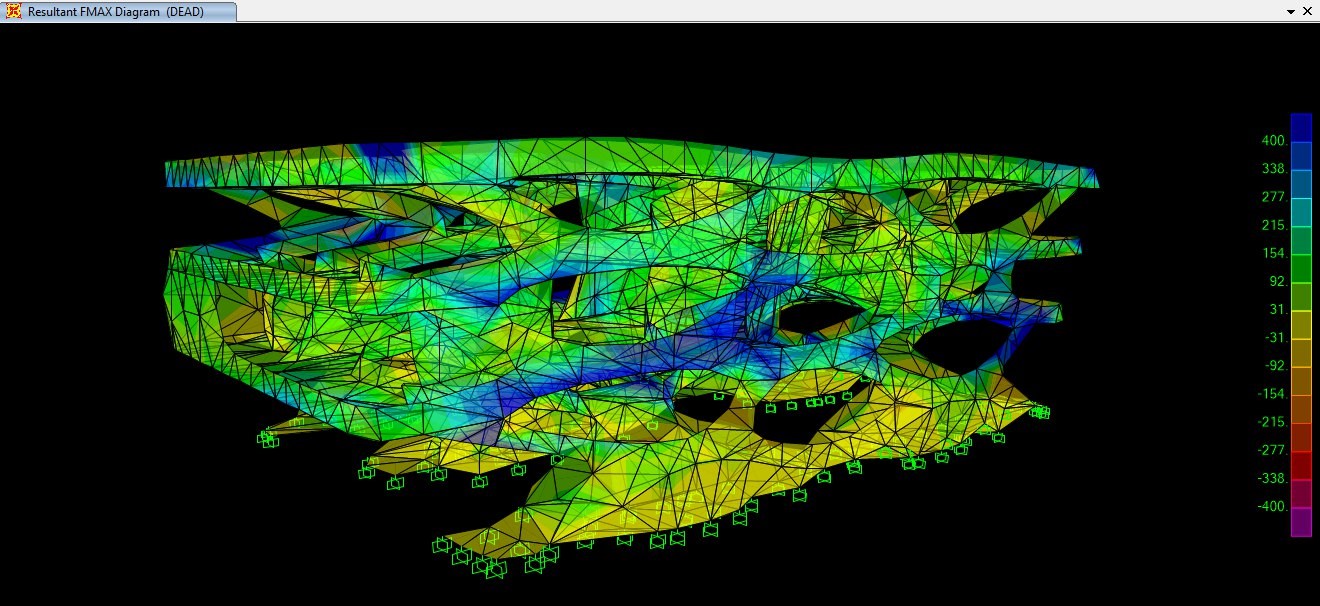

The Dutch Pavilion is one giant connection machine. Everything connects to everything through the spatial web of physical connections, each building component connects to its neighboring components. In analogy, like birds connect to neighboring birds in the swarm. The parametric One Building One Detail design strategy guarantees the integrity of the connections. The parametric design is directly linked to the CNC production of the perforated steel components. Scripting architecture means that either everything fits or nothing fits, what becomes already clear in the early design phases, and maintains its integrity throughout the whole design to production process. From the initial parametric sketch our fundamentals are defined to fit precisely, such that each and every unique component bearing its own unique number is assembled in just that single unique position in that specific order and for that specific reason. The base component of Do by Dutch is a triangular sheet of steel with flanged edges, folded or welded to the triangular base, whichever proves to be the most effective. Simply by bolting the all-inclusive components together the building will self-erect, no scaffolding needed. The Do by Dutch pavilion is a self-building building. In each stage of the assembly the structure is perfectly rigid and safe to work upon, or to hang from. The assembly can be done by small teams of relatively low skilled workers, basically two persons can assemble a component, one steering a small robotized aerial platform to lift the components into place, and one to fix the bolts. In fact, the whole process of assembly could be robotized completely since the same procedure repeats all over, using varying parameters. Imagine having small mobile crawling robots, one to maneuver the component in place, and one to fasten the bolts. The One building One Detail method paves the way for a fully robotic production and assembly. For example, when one would want to robotize a traditional building method, one would need an army of different robots to do the job, while there are so many different elements in a traditional building, and so many different ways of connecting the elements. Especially the wet connections that still prevail in traditional building methods, are difficult if not impossible to automate. I am seriously looking forward to getting a building like the Do By Dutch commissioned to deliver proof of the uncompromising parametric design to robotic building to robotic assembly process. Robotic production and assembly will certainly pay off in terms of budget, time, robustness, and aesthetics. From component to component, we designed transitions from maximum open to fully closed. Where there is more material needed to transfer the gravity loads and dynamic wind forces the components will be more closed, more robust. The material is only there when and as needed. Where more openness is required, typically in the components formerly known as balustrades, we opt for larger perforations. Where integration of exhibition items is required, there are inlays embedded in the components, as the seating pads in the Body Chair. Where climatic compartimentalization is required, the components are closed or glazed, enclosing a space. There the components are doubled to include the required insulation. The basic component is further specified where and as needed. Where a bigger platform is needed, the parametric model is adjusted to the desired dimensions. Where ducts and risers are needed, they follow the edges of the components, synchronized with the structural components, similar to how in the Cockpit building the sprinkler system follows the horizontally stretched tension profiles of the structural skin The patterns of the perforations are parametrically linked to the shape of the components, as in the Climbing Wall. The patterns are resonating with but not copying traditional Arabic patterns. The structural performance of the components is calculated using a finite elements method by the Central Industries Group [CIG, formerly Centraalstaal] in Groningen, The Netherlands. We have worked with this company since the Fside housing project [2007] which was, as mentioned earlier, their first architectural scale project before they conquered the world. The outcome of the finite element analysis for the Dutch Pavilion underpinned CIG’s competitive financial bid, their price was within budget, which is quite exceptional for such a radical design.